SBIR Reauthorization: A needed reboot or a punt?

Part 3/3: It's 11:59 PM and the small-business reauthorization set to expire. Let's look at what will change, what will not, and what it means.

Author’s Note: The past several months have been an interesting ride that is coming to an end. I’ve had the opportunity to engage dozens of people in the DOD, Congress, lobbyists, defense investors, and tech companies on this topic. Unlike my policy work in past lives, I have no official role or sponsor for my analysis, summaries, and killer memes. And yet, all parties have been gracious with their time, input, support, and criticisms. Thank you.

Special shoutout to Sam Lau, best illustrator out there!

TL; DR

The Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (OUSD(R&E)) recently announced the first set of projects to receive funding via the pilot program to Accelerate the Procurement and Fielding of Innovative Technologies (APFIT). Ten DoD program offices will receive $10 million in APFIT funding for ten small businesses or nontraditional defense contractor vendors. It’s an exciting program and is receiving buzzworthy press. It should. It will accelerate and field new capabilities, and will bring promising technology companies closer to the DOD, and will stimulate their growth as economic engines for our country.

And yet, in the backdrop of the SBIR/STTR reauthorization, APFIT is a bit of a “let them eat cake” moment. Why? Because of all of the promise and potential of APFIT, simple reforms to the SBIR/STTR set-aside could fully fund 2-4 APFITs programs, 20-40 companies…every year. That’s worth a pause and reread.

For a refresher, read the overview of some of the issues and the deep dive on SBIR mills. Quick summary: across all SBIR agencies, five companies repeatedly consume over $100M annually in Phase I/II awards, the top 30 companies consume $300M annually, and the top 50 about $475M per year. These companies are viewed as champions and the conventional competitions fair, but indicators call that into question:

After 37 years and $573M of SBIR/STTR funding Physicial Optics Corporations, the highest awarded SBIR company, sold for $310M.

Publicly-traded Luna Incorporated recently sold its Labs division for $21M. Reportedly, Labs’ work represents the majority (95%) of Luna’s SBIR awards ($198M), which would mean it roughly sold for what Luna received in awards last year, and a tenth of Luna’s overall SBIR funding.

Creare LLC, the case study darling for SBIR, has received $432M yet still roughly employs 100 people each year and has returned $0.47 on every DOD dollar invested.

When reviewing the traditional SBIR selection process, fair competition, and best-in-class companies working in the DOD:

A recent GAO report shows that in the open topics in SBIRs out competes conventional approaches, a promising sign for the AFWERX program.

While extreme, the week old Daily Beast article shines a negative light on SBIR selection process and “fair competition” for awards.

Many emerging tech and heavily vetted companies that work with other well-known DOD programs are just not interested in pursuing SBIRs for the reasons previously covered. Only 11% of In-Q-Tel backed companies and 23% of DIU companies have also been awarded SBIRs.

A large part of the issue at hand is the internal debate at the highest levels of the DOD and Congress on the core purpose of the program. Some consider the purpose a basic R&D function, no different than DARPA or the national labs. Others see it as a way to transition technologies and stimulate economic growth. Some just see it as a way to spend O&M dollars. The nebulous purpose means that in each reauthorization conversation, the people in the room may have wildly varying perceptions of objectives, success criteria, and paths forward. Until leaders can align, SBIR/STTR won’t know where it’s going, so any road will get us there.

Though I’m personally pursuing SBIRs and STTRs for my own company — I want to reshape how the DOD works with very large AI architectures — I’m not sure I support the reauthorization if there is little reform. I’ve done a lot of analyses on this topic, won and lost SBIRs and STTRs, and been in the room for the reauthorization debate. I believe we can do better for the warfighter and the taxpayer than what will likely transpire. With that positive spin, let’s cover:

a prediction of what will, will not, and should change with the reauthorization,

a review of the SBIR champions that are inspiring the status quo,

a brief discussion of selection bias and lost opportunities,

my final recommended reform recommendations.

Seeing into September

With a handful of days/weeks left until reauthorization, here’s a prediction of what will/will not change in the reauthorized bill. Some specifics are being closely held, but I can project with a fair degree of certainty….(drum roll)….it will be reauthorized soon, and very little will change. It’s an election year and a near-recession economy, so I believe it’s unlikely that Congress will rock the boat…even if it should. Let’s review the details.

Where are we today? The current program benchmarks focus on Phase I/II transitions and Phase II performance. Firms with >20 Phase I awards/5 years must transition 25% to Phase II. Firms with >15 Phase II awards/10 years must: average > $100,000 of sales and/or investments/Phase II received or have received a number of patents — 1 patent/7 Phase II awards. In practice, none of the “performance requirements" prevent abuse or are hard to achieve, so there is room to tweak the benchmarks and not displace the status quo.

The summarized table below includes the current benchmarks, the estimated future state, and my recommended policy changes, which are similar in nature to other proposals that are in flight but not in the public domain.

What you will likely see: marginal tuning to current benchmarks. I anticipate the reauthorization will increase transition targets from Phase I to II and II to sales/patents. This is directionally useful, but it will allow all SBIR firms to continue to “compete” and consume an outsized share of dollars with little return.

What you will not see: annual limits or overall program limits. By using some form of limits (my recommendations are examples), a small subset of firms would exit the SBIR program and would need to compete for commercial contracts. Hundreds of millions would be freed up for new innovation, and the changes could be the largest catalyst in small business DOD funding — funding 30 to 40 companies with APFIT style contracts, or hundreds of companies with traditional Phase IIs. An even more radical/useful idea would be to use the freed-up money from limiting mills to fund Phase IIIs. Unfortunately, I anticipate any form of limits to be off the table.

Other things to watch. 19 tech companies wrote a joint letter to Congress pushing for reforms to SBIR/STTR, including allowing tech companies that are majority owned by VCs to participate. Given we allow public companies to compete, I don’t understand the logic behind excluding these additional firms. However, this is a relatively new ask, and will not be accepted given the short timeline.

The 19 firms also pushed for multiple Phase 2 awards to be allowed as follow-ons to the first Phase 2. In a perfect world, I agree this would be a good extended bridge given the pace of DOD procurement. Given the reality of the SBIR mills, I think this is a terrible idea unless other reforms are put in place as it will likely enable the few companies to consume even more of the total set aside.

One final thing. Right now the reauthorization is supposed to last five years. Given the recent focus on the program and the push for change, I could see any reauthorization time window coming in a bit, say for 2-3 years.

In summary, I believe the SBIR/STTR reauthorization will happen soon, and will largely behave as it has in the past. I’m guessing that none of my recommendations will take hold this reauthorization, but we’ll get ‘em next time! It will be a missed opportunity for the DOD, emerging tech companies, and defense investors. The SBIR champions (mills) will keep on producing mixed results, so let’s take a look at what we’re in for and why I’m not bullish on their results.

Bring forth the champions

Reviewing the best companies of the SBIR/STTR program, it is easy to point out some great companies. Qualcomm Inc received $1.5M and now has a market cap of $175B. Anduril Industries has received $12M, and while still private, is likely worth between $7-9B, Shield AI received $2.3M and has a recent valuation of $2.3B. Billions in future DOD and USG contracts have or will be awarded to these companies and they should be the blueprint for the DOD SBIR program — early limited support to help incubate innovation and dual-use technologies and deliver significant capabilities.

Not all of the SBIR champions offer the same level of success for the DOD. Let’s touch on Physical Optic Corp and Luna Innovations, then do a deep dive on the all-time favorite Creare LLC.

Physical Optics Corporation has received $577M in SBIR/STTR funding, $360M of that from the DOD. It has generated $580M in DOD non-SBIR contracts since 1987 and has 22 patents of interest by the USG. The company recently sold itself for $310M, or 53% of the non-dilutive investment dollars received from the SBIR/STTR program. While the company has likely delivered successful support to the DOD, at $26M/patent and 53% of the non-dilutive funding a good government investment?

Luna Innovations Incorporated was featured in the previous post. An important additional note is that like Physical Optics, Luna recently announced that it sold off Luna Labs -- the division that was awarded so many SBIRs -- and announced that SBIRs will soon represent less than 5% of their future revenue. This is a poor outcome for the DOD given Luna received $21M in 2021 and over $200M in SBIR awards. How could the companies that receive so much be worth/sell for so little?

The curious case of Creare. Creare LLC is cited as a champion of the SBIR program and is featured in several case studies — particularly with the Navy. The company is a ~100-person engineering firm formed in 1961, began receiving SBIR/STTR funding in 1983, and has not missed a year since. In total, Creare has received $432M of SBIR/STTR awards, with $277M of it coming from the DOD. They have also generated an additional $130M in contracts from the DOD and 23 patents with government interest. Finally, they proudly tout the five spinoffs of the company from their history. So if the Navy seems happy, why should we care?

Undelivered value to the DOD - If we consider a spin on ROI calculations — Defense Return on Defense Investments (DRODI) — Creare is $130M / $277M, or 0.47. Is that a successful investment for the DOD? Unfortunately, Creare is not a one-off as ~70% of the top 35 awardee companies have DRODI < 1.0.

Pricey innovation - Patents are a loose signal of innovation, but not nearly as useful as they were decades ago. With 42 patents, 23 of interest to the government, the cost per patent from SBIR funding is between $10M-$18M.

Questionable economic growth - the dependency on SBIRs tends to create relatively stagnant employee growth with most SBIR mills, intentionally, so they can continue to be awarded SBIRs. The 100 - 120 total employees at Creare has been a relatively flat number for at least 20 years, and yet each year, they receive SBIR awards averaging around $17M, subsidizing roughly $125 - 175K per employee. To further this point, since 2009, Creare’s averaged $21M per year in SBIR/STTR funding, which is equal to the combined cumulative lifetime SBIR awards to the following companies: Anduril Industries., Calypso AI, Clarifai, Corelight, Primer AI, Rebellion Defense, Second Front Systems, and Vannavar Labs. The latter group employs thousands of employees, and have been awarded real contracts that far exceed Creare’s entire revenue stream with the DOD. So why continue to choose one over so many?

Finally, let’s consider one last topic: the well-vetted DOD small businesses that aren’t touching SBIRs.

Selection Bias and Opportunity Costs

A consistent theme during the reauthorization process has been a belief that the best competitor always wins the awards. SBIR mills use the best-in-class theme as a justification for their consistent haul of awards, but as previously discussed, often cannot reconcile the lack of actual contracts and a strong DRODI.

The GAO Open Topic report may further encourage the use of open topics to stimulate competition over the conventional process and yield positive results, yet we’re not often considering whether the best small business technology companies are even participating in the program. Quantifiably, that answer is no.

Two DOD-affiliated organizations, In-Q-Tel and DIU, help demonstrate the gap. In-Q-Tel (IQT) is the independent, not-for-profit strategic investor that links the U.S. intelligence community to cutting-edge technology solutions. IQT has worked with roughly 350 companies since 1999, so if we believed that the SBIR/STTR program was consistently capturing the best defense-related companies, we would assume a large overlap of heavily-vetted IQT and SBIR companies. Unfortunately, that is not the case. Only 13% of the publicly announced IQT companies also received SBIR awards, and while not all IQT companies went on to be defense unicorns, it is fair to assume the great majority were eligible to participate in SBIR/STTR, but chose not to engage.

Defense Innovation Unit, formed in 2015 provides a smaller but relevant sample. Since inception, only 11 of the 47 known DIU awardees have also received an SBIR award. A higher percentage than IQT, but still an indicator that many companies that can go after SBIRs are not even bothering to do so.

In all the conversations of the great companies already participating in SBIR/STTR, it is easy to think about only the companies that are part of the known sample. It’s not easy to think about what companies are not participating. We look at the handful of spin-offs of Creare in 40 years, not the defense unicorns that never engaged with the program or ones that never had a chance to make it because of the faults in the process— that’s selection bias.

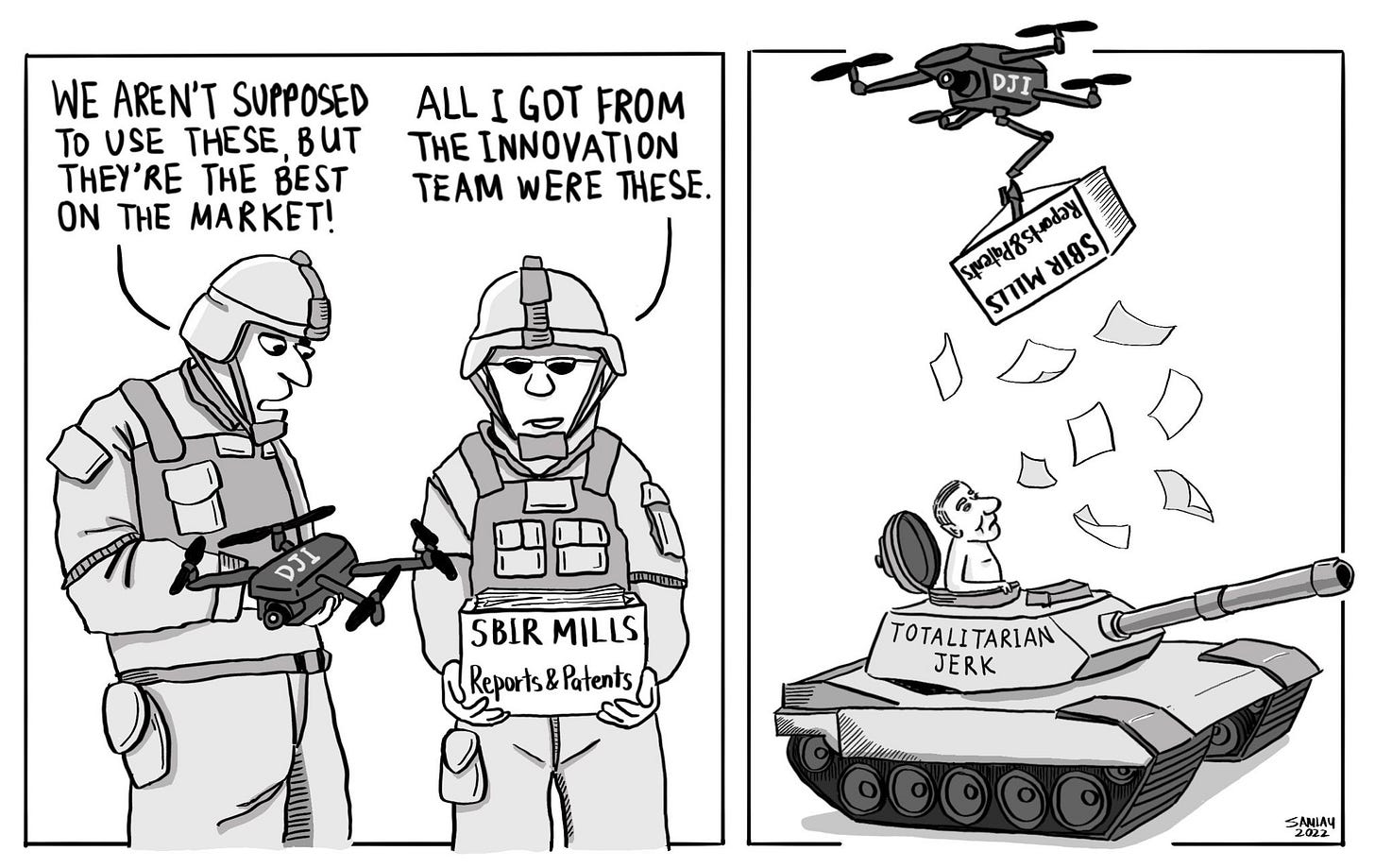

Moreover, it’s even more painful to think about what capabilities might have been delivered if the best in class emerging defense technology companies always participated early in the SBIR/STTR program. Early cheap commercial drones, cutting edge AI, next-gen semiconductors— that’s an opportunity cost for the warfighter and our country.

This brings us full circle to APFIT and the end of this series. I’m fully confident that the DOD has the ability to find great companies and game-changing technologies for the warfighter. APFIT, DIU, and IQT are all examples of programs that I believe in as part of the solution. However, I do not have confidence that a reauthorized SBIR/STTR program with little reform will deliver the same type of capabilities with far more resources.

Without further ado, my final final list.

The final final list

While I don’t think any of my recommendations will be implemented this time around, I am confident that smarter people will continue to ask great questions and look at the data, and we will find a better way to reach the potential of the SBIR/STTR program. Here are some things to consider:

SBIR/STTR leaders — decide what you want this to mean for the DOD, basic research or innovation and transition. If all of the above, it will remain confusing, lack real objectives, and will be susceptible to abuse.

$75M program limit for any company. This is an insane amount of money for any growing firm to develop multiple products and build all the DOD infrastructure to succeed and thrive on its own. Anything beyond that total and companies are addicted to the funds, will stagnate, and need to be cut off.

Annual 8/4/2 Awards — Limit the number of annual awards per company 8 Phase 1, 4 Phase 2, and 2 (tacfi, stratfi transition dollars).

Remove > 50% VC ownership restrictions, this is silly, particularly if public companies can participate.

Consider publicly traded company limits. What if Luna was giving a dividend each quarter using taxpayer grant money? That just seems off.

Make the application process easier and provide better guidance on topics important to organizations. Transparency and communication would encourage more open topic entrants, simplicity will decrease likely disqualification for silly reasons.

Deeper connections to the PEO, the use of OTAs, and other pathways to navigate the post Phase 2 valley of death.

Thank you for reading the series, for all of the feedback, comments, and corrections. To the civilians and men and women in uniform, thank you for your service.

There are more policy, defense, and AI topics I’ll cover in the next few months. Subscribe or just connect with me on LI or follow me on Twitter.