Author’s note: I got sucked into this vortex during the last reauth in '22. In this go-around, the policies are meaningful and should be supported, so I dusted off my Excel skills, and I'm back. This article is the first of three outlining the state of affairs with SBIRs and the 2025 Reauthorization; the next will focus on the impact of INNOVATE, and the third will be where the chips eventually fall by September.

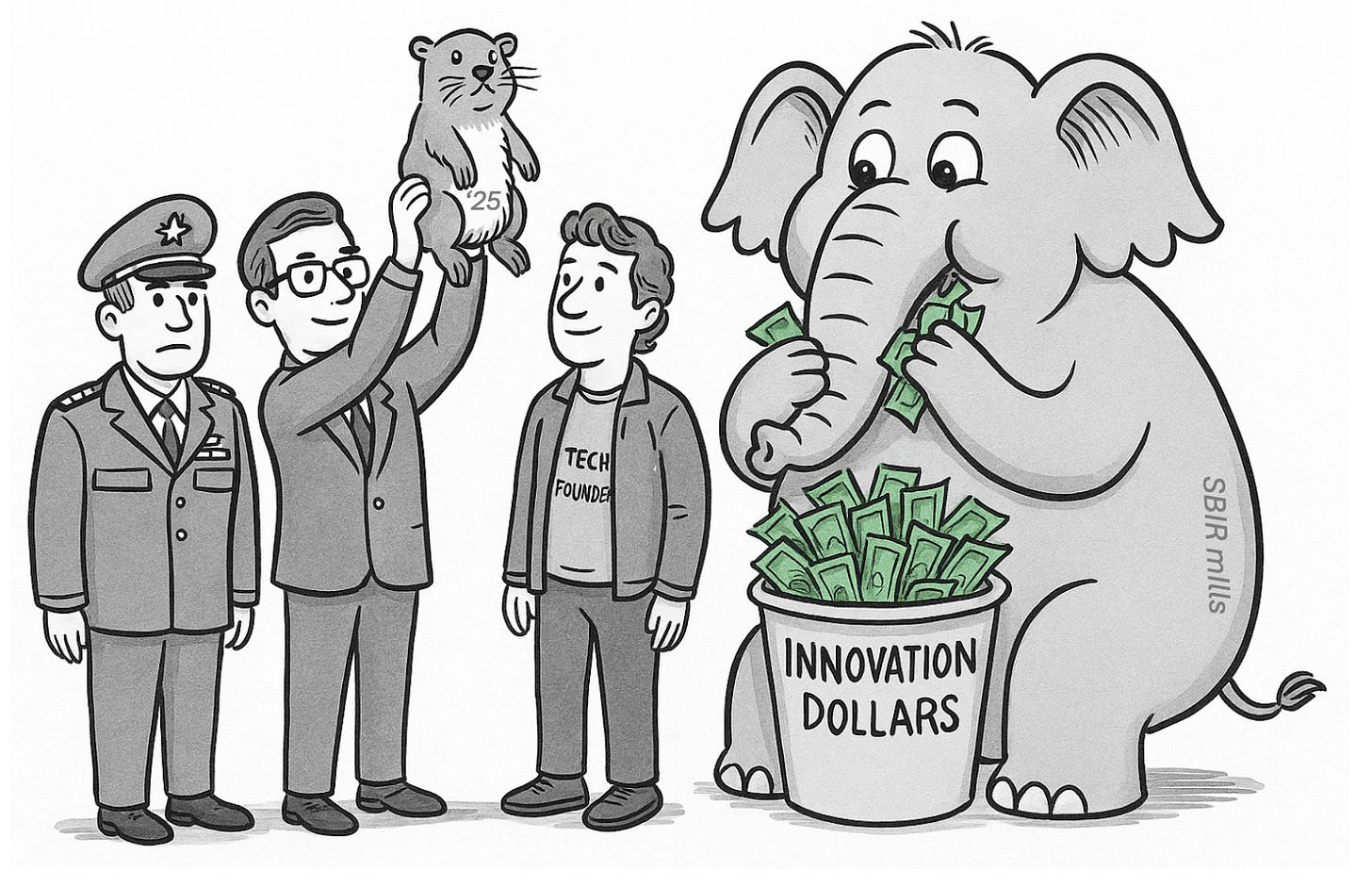

Every few years, the SBIR program wakes up to the same tune. Policymakers scramble to reauthorize a $4 billion-a-year seed fund for small businesses, the defense innovation crowd gets excited or enraged, and then—usually—the program is renewed with barely a nudge toward reform. Welcome to the Department of Defense's Groundhog Day.

But this time, there's a twist: Congress has two very different visions on the table for SBIR's future. One offers the familiar rhythm of the past. The other—the INNOVATE Act—proposes a serious shake-up. Whether we loop back into mediocrity or move forward may depend on which path wins out.

Wait, what is SBIR again?

The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs channel over $4 billion annually into early-stage R&D. More than half of that goes through the Department of Defense. In theory, these programs do two things:

Help small businesses survive the nightmare of working with the Pentagon.

Turn promising tech into prototypes, and prototypes into fielded capabilities.

In practice? Not quite.

Same script, same cast

For years, the same companies—dubbed "SBIR mills"—have dominated the funding landscape. Just 100 companies have received over $6.3 billion in DoD SBIR funding since 2016. Yet these firms rarely transition their tech to operational use. One study found that fewer than 6% of SBIR recipients generate more downstream defense revenue than they get in Phase I/II grants. That number doesn’t exactly scream efficiency.

Meanwhile, many of the most promising, venture-backed defense startups skip SBIR entirely. Companies like Anduril, Shield AI, and Vannevar Labs—despite building products the Pentagon actually buys—have yielded SBIRs (including STRATFIs) of $12 million, $4 million, and $2 million, respectively. Why? Because the process is slow, unpredictable, and heavily tilted toward incumbents who know how to play the game.

Enter the INNOVATE Act

The INNOVATE Act (Investing in National Next-Generation Opportunities for Venture Acceleration and Technological Excellence) is a bipartisan proposal led by Sen. Joni Ernst. It would reform SBIR by targeting three core problems:

Too few new entrants: INNOVATE would create a "Phase 1A" track—a simplified, $40K award with a 2-page application, reserved for first-timers. It could support up to 2,700 new companies a year.

Too little transition: The bill creates "Strategic Breakthrough" Phase II awards of up to $30M (matched by private capital) for companies with real traction and a committed DoD customer.

Too much deadweight: Firms that receive more than 25 Phase II awards would need to show $1 of non-SBIR revenue for every SBIR dollar received. Lifetime SBIR funding would be capped at $75M per company.

This is not radical stuff. These are basic standards: bring in new talent, scale what works, and stop subsidizing companies that never graduate.

Who's against this?

Predictably, the old guard. Some argue SBIR mills have produced useful technology, and that complex DoD procurement processes make transitions hard even for good performers. That’s fair. But it doesn’t justify the current imbalance.

Studies show that most mills underperform on commercialization. A 2023 GAO report found that firms with more than 50 Phase II awards generated less downstream revenue than those with fewer awards. Even using generous definitions of success (including subcontracts), only about half of the top 25 mills broke even on their SBIR dollars.

And it’s not just about ROI. It's about opportunity cost. Every dollar going to a company with a 0.47:1 return is a dollar that isn't backing the next SpaceX, Palantir, or Saildrone.

VC Clock Is Ticking

Venture capital has been flooding into defense tech startups over the past few years – but that flood won’t last forever, and the SBIR reauthorization will play a role. Between 2020 and 2024, annual VC investment in defense-related technology nearly doubled, reaching record heights in 2024. Globally, defense, security, and resilience startups secured about $5.2 billion in venture funding in 2024 – up 24% from 2023 and almost five times the level of 2019. In the U.S. alone, VC-backed defense startups raised roughly $3 billion across 100+ deals in 2024 (up from about $2.7 billion in 2023).

That said, today’s venture momentum is strong but conditional. Venture capitalists are pouring money in because they see potential, but they’re also watching carefully to see if Washington can clear the way for that potential to turn into big wins. Many of the leading defense startups and their backers have made it clear that policy reforms are needed to keep this virtuous cycle going. In fact, 19 tech firms – including some of the biggest new defense players – even wrote a joint letter to Congress urging SBIR changes, like allowing venture-backed companies to fully participate in the program.

The INNOVATE Act represents exactly the kind of reform VCs are hoping for: provisions like Strategic Breakthrough matching funds up to $30 million would help bridge the notorious “valley of death” by pairing SBIR dollars with private capital. Changes like these signal to investors that a startup’s groundbreaking tech won’t languish for years in procurement purgatory. Without such reforms, there’s a risk that today’s enthusiasm could falter. Remember, the only reason many investors stayed away in the past was the slow, byzantine acquisition process.

Groundhog Day or breakthrough?

The SBIR program needs to evolve. It’s no longer 1982. The U.S. isn’t the only country funding dual-use innovation. Our adversaries are integrating commercial tech into defense at breakneck speed. We can't afford another six years of business as usual.

The INNOVATE Act offers a path forward. It preserves the good intentions of SBIR but aligns incentives with outcomes, and it encourages private capital to continue to participate in the defense industry by opening the door for more ambitious startups and gives DoD a real shot at transitioning technologies that matter.

This is our chance to break the cycle. Let’s not waste it. Because if we do, we know exactly what happens next.

[Alarm clock beeps.]

Same day. Same problems.

Ben Van Roo is co-founder and CEO of Legion Intelligence, which delivers secure agent-orchestration platforms for mission-critical AI deployments across defense, government and enterprise networks. He holds a PhD in Operations Research, an MBA and a BS in Computer Science and Environmental Engineering from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Before Legion, he held executive roles at multiple startups and conducted defense research at the RAND Corporation.

Ben, great article. I would argue that there is a responsibility on the side of the government to ensure that actual requirements are tied to SBIR/STTR topics, which the INNOVATE Act also addresses. RIght now, any technical lead can generate a topic, regardless of whether there is any funding or acquisition tail associated with the project. It's not the fault of SBIR mills that some of these are "science projects", with absolutely zero chance of getting more federal dollars after SBIR money runs dry. Low TRL projects are also tough to transition - as you've previously mentioned, '80's level funding and the current SBIR timeline doesn't allow for DARPA-like efforts that will likely take 15 - 20 years of R&D to bear fruit. The risk assessment from the government side on whether to pursue these projects using SBIR dollars is skewed because of the perception of SBIR being "free money", or worse, a "tax" on the budget that must be clawed back regardless of ROI.

💪💪